In order for creative placemaking to be successful, it needs to be intentional and there needs to be a strong focus on design, community engagement and collaboration.

“Creative placemaking is both a philosophy and it’s a process that can help shape community. It can help create a sense of belonging, a sense of community and it can certainly enhance place distinctiveness,” explained Tim Jones, former CEO of Artscape, in a recent webinar entitled Extraordinary Achievements in Creative Placemaking, hosted by the Urban Land Institute.

“These are the things that most make places attractive to people, but they also determine the value of places both culturally and financially. It’s really important to recognize that these things don’t just happen by magic.”

Creative placemaking in Toronto

One of the projects that exemplifies creative placemaking is Toronto’s Distillery District.

“There have been many failed attempts to bring this place back to life,” Jones explained.

“It was purchased by a company called Cityscape in 2001 and they adopted a strategy of using the arts as the main driver of the redevelopment process.”

Galleries, theatres and other arts groups got on board, he added.

“What was imagined to unfold over eight years happened in about 18 months,” Jones said.

“The momentum that was created by the artists involved…the narrative that started to emerge about this project was really strong and positive and helped to dispel a lot of skepticism.

“We threw an opening party and 70,000 people showed up. That’s when the penny really dropped for me about the power and the value of arts and culture to actually effect change in urban and community development. We learned so much about how it can be done in different places to achieve different results.”

While creative placemaking is sometimes used for cultural purposes, there are many examples of it being used for community revitalization.

“Any of us who have worked in community planning and development, one of the things that’s hardest for folks is to imagine is that tomorrow can be different,” said Jamie Bennett, interim president and CEO of United States Artists.

“If you’ve experienced a neighbourhood and it’s been in the same kind of disinvestment, if it’s been in the same condition for years and years and years, it’s really hard generationally to get folks to believe that tomorrow can be different, to create the will to do some of these great developments.”

‘Changing the narrative’ in Regent Park

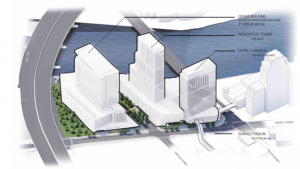

The Regent Park revitalization in Toronto is another example of creative placemaking.

Jones said Daniels Spectrum, a community and cultural hub by Artscape, Toronto Community Housing, The Daniels Corporation and members of Regent Park became the “heart” of the project and was “central to changing the narrative in the community.”

“The chief instigators of revitalization in the community said to us one day, ‘We get how people think and talk about Regent Park. They read about us in the newspaper,’ ” recalled Jones. “ ‘What if we actually created a place here that made it normal to come to Regent Park. Not just a place for culture as a local resource but a place that is rooted in Regent Park and open to the world.’ That really inspired the vision for the larger project.

“The impact that this has had over the last 10 years has really been phenomenal.”

Although the idea came from the community, it didn’t immediately resonate with them.

“When it was built it didn’t automatically resonate with the community that existed in Regent Park right away,” said Heela Omarkhail, VP of social impact with The Daniels Corporation.

“Building the building is great. Creating the programming that responds directly to the community needs is better. When we think of placemaking, it needs to both respond to the place but also to the people.”

Transforming construction into creativity

Bennett described how the community in St. Paul, Minn. came together to find creative ways to bring people to the city while the expansion of their light rail transit system was taking place.

“What this local group did is they worked with 600 local artists and they trained them on how to self-produce and how to partner with small businesses and community organizations,” Bennett explained.

“Over that 18-month construction period they sent them out and said, do whatever your art practice is, just do it along the construction corridor. Those artists produced events that ranged from a jazz concert in a Thai restaurant, to a dance lesson in a parking lot, to a stained-glass visual artist installation on a construction fence. What they discovered essentially is that those artist interventions totally changed the narrative of what was happening in that neighbourhood.

“It was no longer the terrible neighbourhood to live in. It was the happening place.”

Follow the author on Twitter .

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed